Constitution DAO, Emotion Recognition Technologies and how to say ‘I don’t know’

Hi there,

As I sat down to write this week’s newsletter a few days ago there were a handful of areas I wanted to explore. Rather than narrow it down and do a deep dive into just one, I thought I’d try something a little different and briefly explore four things that have caught my eye (plus the usual dose of ‘something a bit different’ to wrap up). Let’s dive in…

—

‘We The People’ - ConstitutionDAO hits trouble

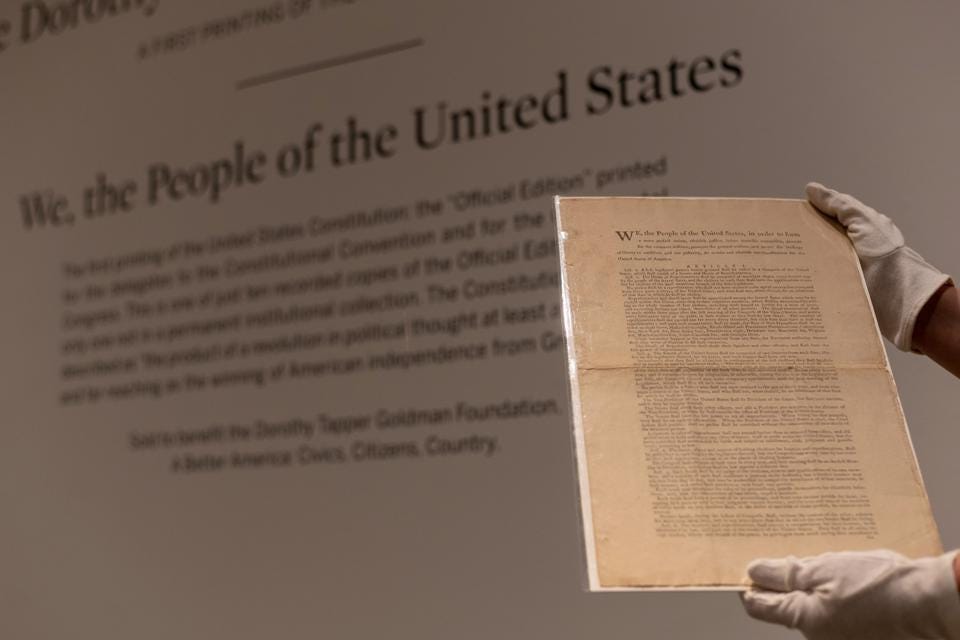

When, in September, Sotheby’s announced the sale of a copy of the US constitution, it sounded like a usual big ticket auction house item.

That is, until a group of strangers came together online and decided to pool all their crypto, using a decentralised autonomous organisation (DAO) to buy the Constitution. With 13 copies of the constitution still in existence, the item is one of only two that are privately owned. The group eventually raised $46m, with the aim of showing that DAOs are hitting the mainstream and planned to show the copy in a public museum, if successful. The DAO was pipped to the post in the auction, but the really fascinating question is: what happens now?

This great Vice piece paints a messy picture. The promise of DAOs is that they provide a new form of decentralised decision making, enabling people to vote on how the organisation works and removing middle-men (and the costs often associated with them). That’s missing here, and the Vice piece describes little structure for processing refunds, with many participants seeing most of their crypto contributions being lost to high fees. Beyond this, there’s a core group of co-ordinators and lawyers managing the process - not a decentralised model. ConstitutionDAO was pulled together in a few weeks, so some of this might be a symptom of a rushed process. But, for all the excitement about web 3, it shows there’s still some way to go to make these models work at scale.

Omicron and the attention economy

Over the past few days Omicron has fast become part of the international COVID lexicon. While we wait to learn more about the scale of the threat, a pre-existing crypto currency - also called Omicron - has seen its value soar. By Monday the value of the token had increased by almost 950%.

A colleague shared this great Bloomberg Opinion piece by Matt Levine on this trend. While I’m generally bullish about crypto, and even more so about the application of blockchain-based technology more generally, Levine’s piece is a great take on why we’ve chosen to create digital scarcity. We’re now in a situation where the term ‘omicron’ is being more commonly used in conversation, there’s scarcity and a limited number of ‘omicron’ tokens, and people are essentially buying omicron (the cryptocurrency) because it’s the thing we’re all giving our attention to this week. This is happening even though there’s zero link between the omicron coin and what’s happening with the pandemic. We’ve seen this before with the ‘Squid’ token, which surged with the popularity of Squid Game, before crashing again. There’s almost no regulatory oversight of this kind of activity, so chances are that we’re going to keep seeing these bubbles for the foreseeable future.

Emotion Recognition Technologies and navigating the future of AI…

This week the BBC kicked off this year’s Reith Lectures, with Berkeley Professor Stuart Russell setting out the near and long-term future for AI. While some of the headlines around the lectures have been a little alarming, Professor Russell’s first lecture was a helpful primer on the medium-term opportunities / risks, with the next few lectures turning to military applications, the impact of AI on jobs, and regulating AI for the future.

Much of the news this week has been dominated by the significant questions of AI use in warfare - the FT Editorial Board covered the geopolitics of AI-led conflict, while MI6 chief, Richard Moore, described "adapting to a world affected by the rise of China” and managing efforts to master AI, quantum computing and synthetic biology as the biggest challenge for British security.

As the EU continues to work through its AI Bill - which will likely set the tone for much of the global regulatory landscape - one of the areas in contention is the way that AI navigates emotion recognition. Based on the premise that our external appearance gives away our internal state, Emotion Recognition Technologies are being used in a variety of applications, including monitoring childrens’ facial expressions during remote lessons, with the stated aim of helping teachers personalise lessons.

While the ethical issues are myriad, there’s also debate about whether it actually works… In 2019 Northeastern Professor Lisa Feldman Barrett and a team of distinguished psychologists looked at whether facial expressions really do reflect our emotional states. They found that “people do sometimes smile when happy, frown when sad, scowl when angry…” with substantial variation in how people communicate their feelings across cultures, situations and even “across people within a single situation”. This Verge piece gets to the heart of the issue. As the EU considers banning the use of facial recognition technology by police, and Germany pushes for a broader ban on the use of facial recognition in all public places in the EU entirely, Emotion Recognition Technologies should be a core part of the conversation.

How to say ‘I don’t know’

I was reading through some old notes this week and rediscovered an interview between Krista Tippett and Ta Nehisi Coates from 2017. It’s a wide ranging discussion but one thing that really stuck with me was when Coates was asked by an audience member for advice on how to teach history in a way that’s honest and accurate. He responded with the following:

I have no teaching advice at all. I was a terrible student. I failed my way through high school. I don’t know how I got into Howard University, but I failed my way through that too. I just — I don’t know. I have horrible advice, in terms of teaching. [laughter] I’m serious. Because one of the things that annoys me is, people act like they know everything…

OK, I’m gonna talk about what I don’t know. And listen, here’s the thing that happens. Here’s the thing that happens. You are well-researched and knowledgeable about one thing that you’ve been thinking about a long time and you’ve been reading about a long time. That does not make you well-researched and knowledgeable about all things.

Because I think there’s this tradition — I get this title, “public intellectual,” and I don’t like it, because what it sounds to me is, like, people who B.S. They’re smart about one thing, and so they play into this notion that they’re smart about everything else. I have not struggled with that at all.

I haven’t. I haven’t, and so for me to answer would be to pretend as though I had. If you want to ask me about writing, I can — up one side, down the other. I got you. I’m with you, because I’ve struggled with that. I can’t address things that are not things that I’ve actually struggled with.

We’ve likely all had moments in our careers where we’ve seen people overclaim about their expertise - and the pitfalls that arise when they do. I found Coates’s response a useful lesson in how to acknowledge where our expertise is lacking. By deciding not to weigh in, he sidesteps the temptation of bluffing his way through and manages to underline his credibility in his own field. As a non-technical person working between policy / leadership and technology, I think about this a lot, including where the value of having a broader view comes in handy. My best answer right now is: 1) Really know your value and play to those strengths which, while it may sound obvious, requires some honesty and self-reflection; 2) Get comfortable with ambiguity and openly problem solve and learn in public with others; 3) Find new frames to help those around you look at the problem in a different way - you might just find blind spots and new ways of conceiving an issue (a quick link back to newsletter #3 on ‘how to ask better questions’). I’d love to hear about how you think about this - please do drop me a line.

Something a bit different

I loved this clip of John Lennon, Ringo Starr and George Harrison that’s been making the rounds on Twitter - they went from playing around 30 seconds into this, to having an early version of Get Back within another minute.

This newsletter is still new, and a bit of an experiment. I’d love any feedback in general, and on this slightly tweaked format. If you enjoyed it, please do subscribe or pass it on to someone else who might like it.